Two Brothers, Two Antrim Designs – One Pac Cup Showdown

An article in the July 2024 edition of Latitude 38 — reprinted with permission. For the original article, see: https://www.latitude38.com/issues/july-2024/

“We’re racing for pink slips,” said Jim Partridge of the upcoming Pacific Cup, where hell be sailing against his older brother, Cree. “Whoever wins gets the other guy’s boat,” Jim added, only half serious – we think.

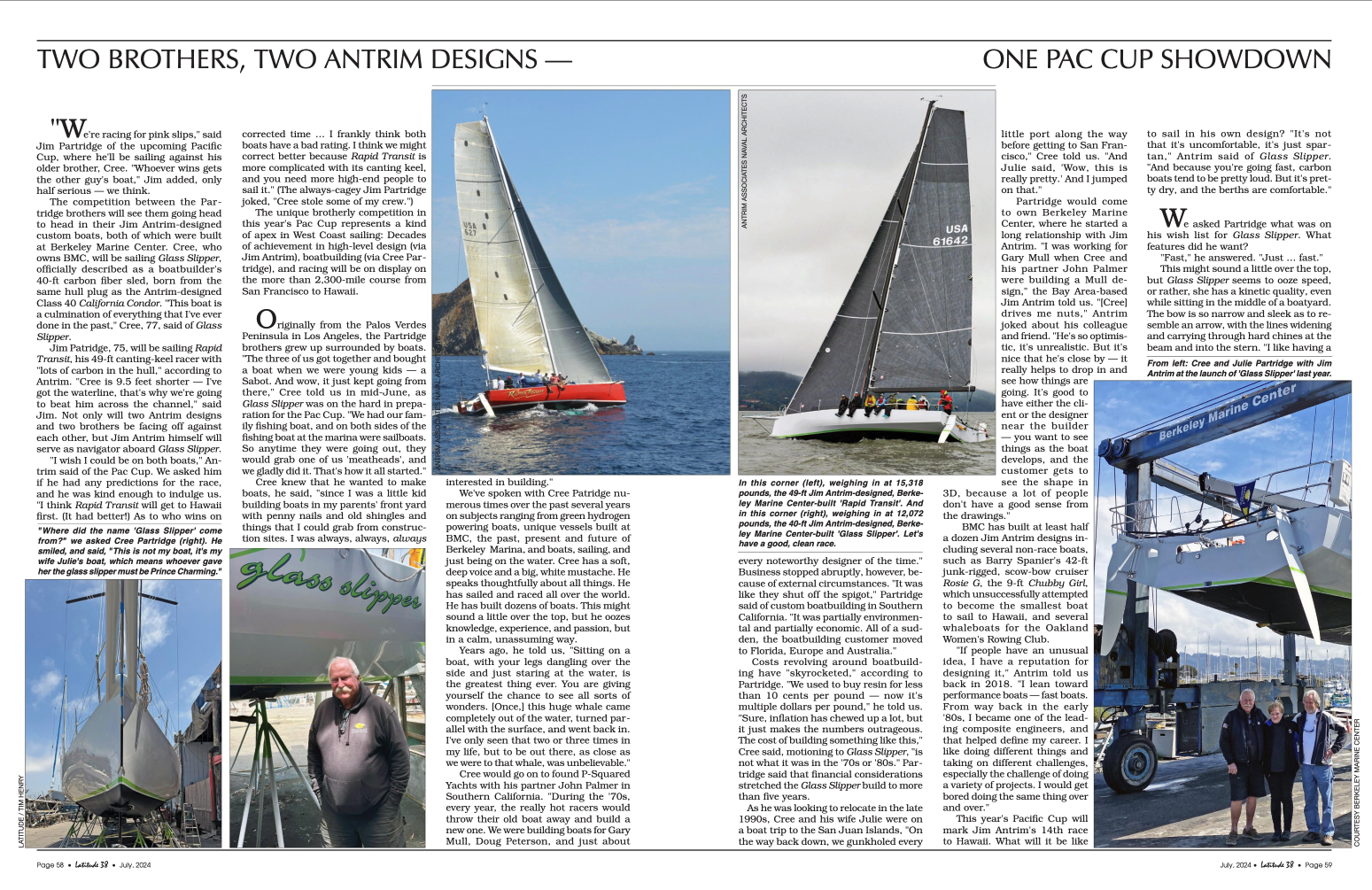

The competition between the Partridge brothers will see them going head to head in their Jim Antrim-designed custom boats, both of which were built at Berkeley Marine Center. Cree, who owns BMC, will be sailing Glass Slipper, officially described as a boatbuilder’s 40-ft carbon fiber sled, born from the same hull plug as the Antrim-designed Class 40 California Condor. “This boat is a culmination of everything that I’ve ever done in the past,” Cree, 77, said of Glass Slipper.

Jim Partridge, 75, will be sailing Rapid Transit, his 49-ft canting-keel racer with “lots of carbon in the hull,” according to Antrim. “Cree is 9.5 feet shorter — I’ve got the waterline, that’s why we’re going to beat him across the channel,” said Jim. Not only will two Antrim designs and two brothers be facing off against each other, but Jim Antrim himself will serve as navigator aboard Glass Slipper. “I wish I could be on both boats,” Antrim said of the Pac Cup. We asked him if he had any predictions for the race, and he was kind enough to indulge us.

“I think Rapid Transit will get to Hawaii first. (It had better!) As to who wins on corrected time …. I frankly think both boats have a bad rating. I think we might correct better because Rapid Transit is more complicated with its canting keel, and you need more high-end people to sail it.” (The always-cagey Jim Partridge joked, “Cree stole some of my crew.”)

The unique brotherly competition in this year’s Pac Cup represents a kind of apex in West Coast sailing: Decades of achievement in high-level design (via Jim Antrim), boatbuilding (via Cree Partridge), and racing will be on display on the more than 2,300-mile course from San Francisco to Hawaii.

Originally from the Palos Verdes Peninsula in Los Angeles, the Partridge brothers grew up surrounded by boats. “The three of us got together and bought a boat when we were young kids — a Sabot. And wow, it just kept going from there,” Cree told us in mid-June, as Glass Slipper was on the hard in preparation for the Pac Cup. “We had our family fishing boat, and on both sides of the fishing boat at the marina were sailboats. So anytime they were going out, they would grab one of us ‘meatheads’, and we gladly did it. That’s how it all started.”

Cree knew that he wanted to make boats, he said, “since I was a little kid building boats in my parents’ front yard with penny nails and old shingles and things that I could grab from construction sites. I was always, always, always interested in building.”

We’ve spoken with Cree Patridge numerous times over the past several years on subjects ranging from green hydrogen powering boats, unique vessels built at BMC, the past, present and future of Berkeley Marina, and boats, sailing, and just being on the water. Cree has a soft, deep voice and a big, white mustache. He speaks thoughtfully about all things. He has sailed and raced all over the world.

He has built dozens of boats. This might sound a little over the top, but he oozes knowledge, experience, and passion, but in a calm, unassuming way. Years ago, he told us, “Sitting on a boat, with your legs dangling over the side and just staring at the water, is the greatest thing ever. You are giving yourself the chance to see all sorts of wonders. (Once) this huge whale came completely out of the water, turned parallel with the surface, and went back in.

I’ve only seen that two or three times in my life, but to be out there, as close as we were to that whale, was unbelievable.” Cree would go on to found P-Squared Yachts with his partner John Palmer in Southern California. “During the ’70s, every year, the really hot racers would throw their old boat away and build a new one. We were building boats for Gary Mull, Doug Peterson, and just about every noteworthy designer of the time.” Business stopped abruptly, however, because of external circumstances. “It was like they shut off the spigot,” Partridge said of custom boatbuilding in Southern California. “It was partially environmental and partially economic. All of a sud-den, the boatbuilding customer moved to Florida, Europe and Australia.”

Costs revolving around boatbuilding have “skyrocketed,” according to Partridge. “We used to buy resin for less than 10 cents per pound — now it’s multiple dollars per pound,” he told us. “Sure, inflation has chewed up a lot, but it just makes the numbers outrageous. The cost of building something like this,” Cree said, motioning to Glass Slipper, “is not what it was in the ’70s or ’80s.” Partridge said that financial considerations stretched the Glass Slipper build to more than five years.

As he was looking to relocate in the late 1990s, Cree and his wife Julie were on a boat trip to the San Juan Islands, “On the way back down, we gunkholed every little port along the way before getting to San Fran-cisco,” Cree told us. “And Julie said, ‘Wow, this is really pretty.’ And I jumped on that.”

Partridge would come to own Berkeley Marine Center, where he started a long relationship with Jim Antrim. “I was working for Gary Mull when Cree and his partner John Palmer were building a Mull de-sign,” the Bay Area-based Jim Antrim told us. “[Creel drives me nuts,” Antrim joked about his colleague and friend. “He’s so optimis-tic, it’s unrealistic. But it’s nice that he’s close by — it really helps to drop in and see how things are going. It’s good to have either the client or the designer near the builder — you want to see things as the boat develops, and the customer gets to see the shape in 3D, because a lot of people don’t have a good sense from the drawings.”

BMC has built at least half a dozen Jim Antrim designs including several non-race boats, such as Barry Spanier’s 42-ft junk-rigged, scow-bow cruiser Rosie G, the 9-ft Chubby Girl, which unsuccessfully attempted to become the smallest boat to sail to Hawaii, and several whaleboats for the Oakland Women’s Rowing Club. “If people have an unusual idea, I have a reputation for designing it,” Antrim told us back in 2018. “I lean toward performance boats – fast boats.

From way back in the early ’80s, I became one of the leading composite engineers, and that helped define my career. I like doing different things and taking on different challenges, especially the challenge of doing a variety of projects. I would get bored doing the same thing over and over.”

This year’s Pacific Cup will mark Jim Antrim’s 14th race to Hawaii. What will it be like to sail in his own design? “It’s not that it’s uncomfortable, it’s just spartan,” Antrim said of Glass Slipper. “And because you’re going fast, carbon boats tend to be pretty loud. But it’s pretty dry, and the berths are comfortable.”

We asked Partridge what was on his wish list for Glass Slipper. What features did he want? “Fast,” he answered. “Just … fast.” This might sound a little over the top, but Glass Slipper seems to ooze speed, or rather, she has a kinetic quality, even while sitting in the middle of a boatyard. The bow is so narrow and sleek as to resemble an arrow, with the lines widening and carrying through hard chines at the beam and into the stern. “I like having a group of people that can sit in the back of the boat at 20 knots and enjoy it, and not tear down on the bow all the time. We wanted the boat wide for the ability to carry as much sail as we could.”

Launched last year, Glass Slipper hasn’t seen much time in the water yet. “We did the Bluewater Bash, and that’s the most we’ve ever been out in the boat,” Cree said. “And we did reasonably well – we were first overall, but we handled the weather very well. There were no breakages of any sort. But I’ve never been so cold and so wet – I retired my foul-weather gear that day. We were getting ‘pooped on’ constantly. In one little surfing episode, I buried the bow clear up to the forward hatch as a big wave was right behind, lifted the stern, and threw us into the trough. But nothing broke.” Cree was quick to note that Glass Slipper was actually not that wet. “It’s relatively dry because of the chines,” he said, adding that at slower speeds, the spray goes straight up. “As soon as you get over 10 or 12 knots, all of a sudden, the spray is gone because it’s going like this,” Cree said, motioning his hands as if over a flat surface. “It’s amazing.”

Jim Partridge said that both Rapid Transit and Glass Slipper “have too much sail on them. But it gets pretty thrilling — I’ve made 32.5 knots,” he told us. Cree was aboard Rapid Transit during a recent Transpac where they sustained 24 knots and above for over 45 minutes.

“Are you at the top of your game?” we asked Cree Partridge. “Are you kidding me?” he responded, shaking his head. “In the ’60s and ’70s, we were vacuum bagging the core and laminating the skin, and we thought, Wow, that’s really something. Look at us.’ Other builders saw what we were doing, and we thought the recognition was really cool.” It was here that Cree mentioned that Glass Slipper was a culmination of everything he’s done, but also, what he can still do.

“I’m constantly thinking about what we can improve or do differently.” Cree is especially interested in scow-bow boats, and foils. “How much advantage/disadvantage are those things?” Cree wondered of foils. “There’s a lot of things you can do with a platform like this [referring to Glass Slipper] to reduce drag and improve upper-end speed and efficiency tremendously, without changing the whole shape, and without giving up safety.”

We asked Cree if there was anything he wanted people to know about him. “I just love doing it,” he said. “I love being part of it. I love helping people do it. And I love to see different people get involved.”

– Latitude / Tim Henry